5 types of fairy-tale retellings

Most children (and adults) love fairy-tales. Oftentimes they follow a simple structure, which makes them easy to remember and repeat. Almost as long as there have been fairy-tales, we’ve had retellings. Cinderella alone has a dozen different versions all over Europe, and Hans Christian Andersen has written some of the most beautiful retellings, such as “The Wild Swans” (Original: The Six Swans). The simplistic elements of fairy-tales are the perfect mould for bigger stories, wider themes, and current issues. They can be easily adapted to transport new ideas. Keeping with Hans Christian Andersen for example: almost all his tales are deeply religious (the little mermaid becomes an air spirit that has to purify her soul), a quality that isn’t necessarily shared by the originals.

Today, we want more than simple plot elements and cookie-cutter character roles. We wish for emotions, depth, and complex characters. And therein lies the beauty of a retelling. Because it becomes a mix of the well-known (and well-loved) and our story needs of today.

Five types of fairy-tale retellings

As part of the collective “Märchenspinnerei”, we have mostly chosen to produce modern fairy-tale retellings. Basically, you can roughly divide fairy-tale retellings into those taking place in a fantasy world, like “Fallen Queen” by Ana Woods or “A Court of Thorns and Roses” by Sarah J. Maas, and those anchored in reality, may that be the modern world, another culture or a historical epoch. Beyond that, there are five subtypes that I want to introduce to you.

1. The classic retelling

Fairy-tales are often short. The characters remain one-dimensional and can be characterised by only a few words: the clever farmer’s daughter, the lazy spinner, the brave little tailor. The plot is told straightforward. There is no explanation for magical interventions, and logic will be sorely missed more often than not. For example, who built the little house the little brother and little sister find in the forest and that nobody ever visits, providing the perfect refuge until the plot moves them along?

Fairy-tale characters have a goal and they set out to complete it. For a short good night story back when you came together at the feet of a storyteller, that’s more than enough. But today, we want more of a story. We want character background, big feelings, and exciting action scenes. This is exactly the spot where classic retellings begin.

They turn a short fairy-tale into a proper novel, provide identity to the characters and beef up the plot. By doing so, they stay true to the original fairy-tale and leave the relationships between the characters intact. There is often a huge amount of world building though: there‘s geopolitics, new plot elements, and a closer look at the society.

Examples: The Wild Swans (Jackie Morris), Beauty: A Retelling of the Story of Beauty and the Beast (Robin McKinley), Fallen Princess (Veronika Mauel)

2. From another perspective

We heard fairy-tales from the hero’s perspective: the poor children who got caught by an evil witch, or the motherless girl who makes a life for herself by being industrious and of good heart, or the good-natured youth who goes out in the world and gets lucky. But what happens to the witch whose house is vandalised and who bakes damn good gingerbread? Or what is the prince thinking, taking home a corpse in a glass coffin?

These are exactly the kind of questions these fairy-tale retellings spin their stories about. They retell the fairy-tale from the perspective of the villain, the love interest, or a common bystander. By doing so, they unearth interesting facets of the main characters that aren’t shown in the original fairy-tale. Some rewrite the story completely. Others stay on a well-known path and give depth to people that remain one-dimensional in the original.

Examples: The Six Swans (Annabeth Leong) – told by the king, The Sleeping Maid in „Beyond the Briar“ (Shelley Chappell) – told by a villager that has been separated from his true love by Briar Rose’s curse, Confession of an Ugly Stepsister (Gregory Maguiere) – told by the evil stepsister

3. The What if-Experiment

Often enough you read a fairy-tale and think about what would have happened if the princess hadn’t waited for her rescue but instead saved herself. Or is Rapunzel still working as a story if it is a young man with long hair that is sitting in the tower? Or what if Cinderella is actually a cyborg?

Many fairy-tale retellings start off with such thought experiments. They take the old material and rework it completely. For example, gender bending stories are very popular. Other likely takes are those that expand on the plain main character and give them some bizarre hobby or job.

Examples: The Lunar Chronicles (Marissa Meyer), Aschenkindel (Halo Summers), the other stories of Beyond the Briar (Shelley Chappell), Thorn (Intisar Khanani)

4. Inspired by

Many times, it’s a particular element that fascinates us about a fairy-tale. Maybe it’s the timeless moral, a relevant message, or a really cool twist. The story of Beauty who falls in love with the ugly Beast alone has spawned a thousand different adaptations. Cinderella, the original industrious girl that gets rewarded in the end, appears in countless stories. It is not necessary for these retellings to be recognisable as such.

Those stories usually don‘t have much in common with the original fairy-tale. The movie Beastly has nothing to do with the original beyond the basic idea and the deadline. For example, the movie focuses more on the character development of the Beast than showing a girl, learning how to love the Beast. A completely different story. Sometimes, retellings only pick up one element (a name, a relationship, a message) and develop something of its own. In any case, this makes for an exciting new story that sets off from the original tale.

Examples: Straßensymphonie (Alexandra Fuchs), Rosen und Knochen (Christian Handel), Rotkäppchen und der Hipsterwolf (Nina MacKay), Alice in Zombieland (Gena Showalter)

5. Modern interpretation

Finally, there is the so-called modern interpretation. In this case, the original fairy-tale is used as a guideline. Those stories adapt as many elements as possible but present them in a completely different setting. This would be where our modern fairy tales from the Märchenspinnerei or similar retellings fit in. It also contains those tales that move their story into Ancient Rome or take them to Japan. It isn’t necessary to adapt all elements of the original fairy-tale or stay absolutely true to the plot, but the original fairy-tale swill still be recognisable if one knows what to look for.

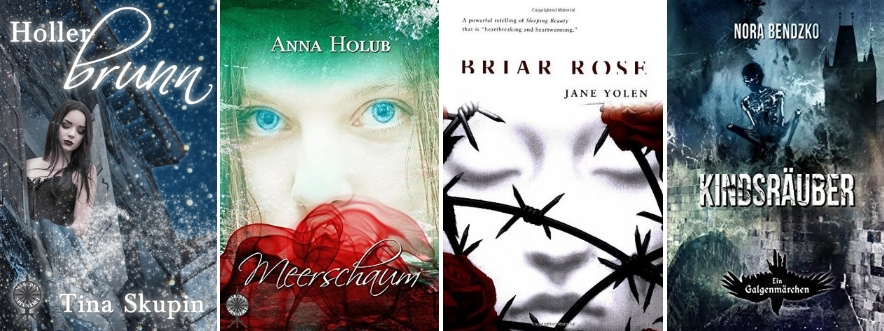

Examples: Hollerbrunn (Tina Skupin), Meerschaum (Anna Holub), Briar Rose (Jane Yolen), Kindsräuber (Nora Bendzko)

No matter whether you are just adorning the original tale or experimenting, with each retelling, it comes down to the basic question: What if?

If you want to know, how I began my retelling of the Grimm’s fairy tale “The twelve princesses/The worn-out dancing shoes” check out this article:

Retelling the worn out dancing shoes

Note: This article has already appeared in an earlier version within the fairy-tale summer on the Random Poison blog.

7 Comments

Agnes

Das ist ein sehr interessanter Artikel!!

Dankeschön

btw ich liebe Märchenadaptionen!

(Meine Tochter nennt sie übrigens beharrliche MärchenAdoptionen, weil sie der Meinung ist, das mache mehr Sinn!)

LG Agnes

Janna

Oh wie süß. In gewisser Weise ist es ja auch so, als würde man ein kleines Märchen adoptieren. Deshalb suche ich gerne welche raus, die noch nicht so viele Interessenten hatten 😉

Liebe Grüße

Janna

Claudi

Hallo 🙂

toller Beitrag. Ich lese total gern Märchen Adaptionen. Zuletzt habe ich “Schattengold” gelesen, das hat mir super gefallen.

Liebe Grüße, Claudi

Pingback:

Nicci Trallafitti

Hey!

Das ist ein sehr informativer und interessanter Beitrag, danke dafür!

Ich möchte demnächst mehr Märchenadaptionen lesen, vor allem die Luna Chroniken wovon ich bisher nur den 1. Band kenne.

Liebe Grüße,

Nicci

Janna

Die Lunar Chroniken habe ich auch noch auf meiner Wunschliste 🙂 Viel Spaß beim Lesen!

Liebe Grüße

Janna

Pingback: